Alchemy of Entanglement: Jemez Lineament of Extraction

New Mexico

2025

Lead Artist: Sarah Ahmad

Collaborator: Andrew M. Taylor

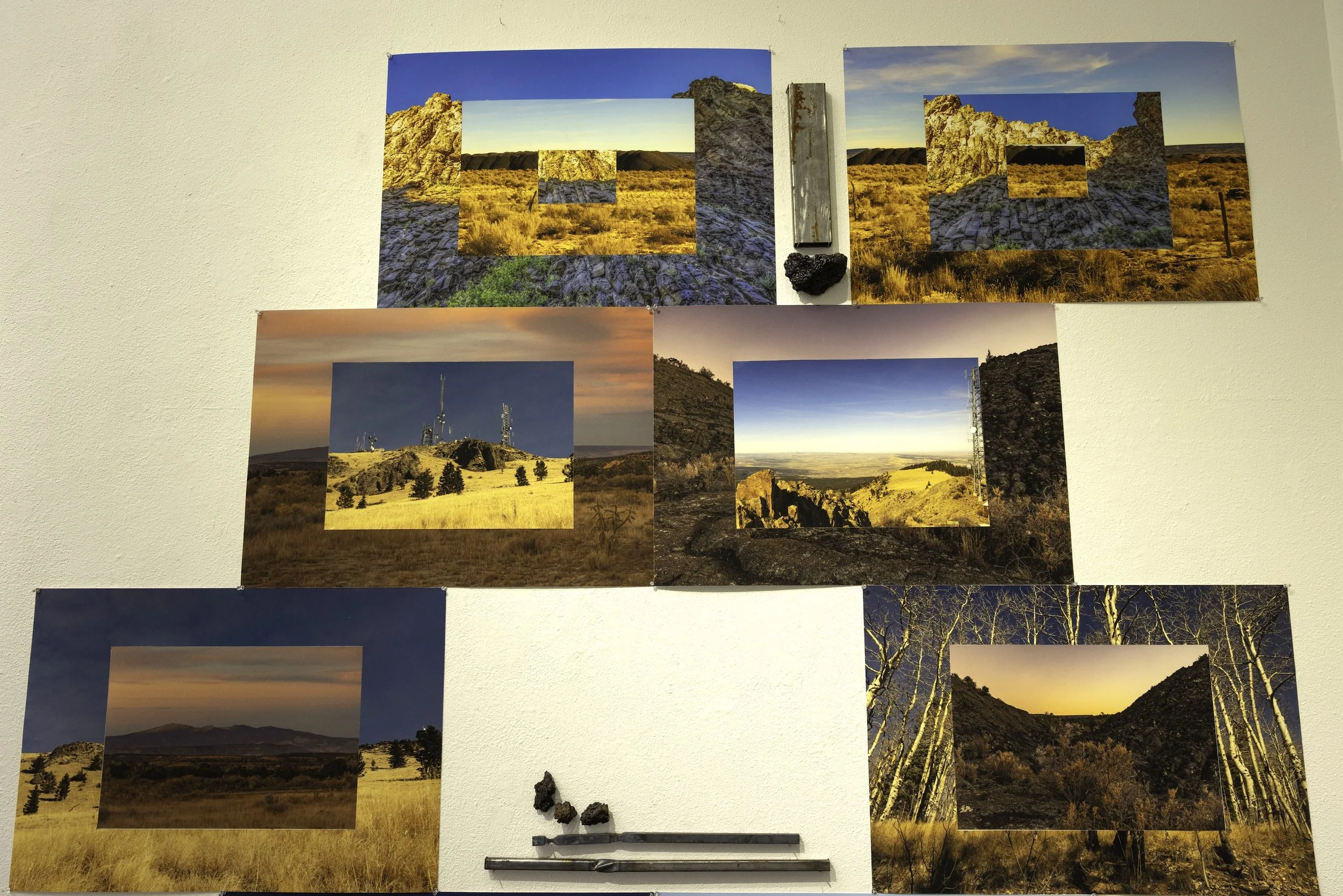

Installation at Santa Fe Art Institute, 2025

Materials: Photo prints on Estrada paper, rock casting, texture rubbings of volcanic rocks and plants on Kozo paper, volcanic ash, acrylic paint, graphite powder, gouache, resin, clay, rocks, iron beams, charcoal and graphite drawings, silicone.

"Matter itself is always already entangled with, the Other… in one's bones, belly, heart. In one's nucleus, in one's past and future." — Karan Barad, 2006

This project explores New Mexico's Jemez Lineament landscape—an ancient crack in Earth's crust that birthed volcanic landscapes and enabled colonial extraction. As non-Natives making New Mexic home for Taylor or temporary home as a moving migrant for Ahmad, we trace this line through Caja del Rio/Diablo Canyon, Los Alamos, El Malpais, Mount Taylor, and Valles Caldera, hiking and documenting through photography, geological and botanical rubbings, clay impressions, rock castings, and drawings. The same geological weakness that created dramatic volcanic features—perfect cinder cones, vast lava flows, eroded basalt cliffs, volcanic tuff canyons, and stratovolcanoes exposing Earth's subterranean matter in sacred geometries of stone—became a lineament of human violence: uranium mining, nuclear colonization, and displacement. We bear witness to landscapes born from geological trauma into sites of wonder, then scarred by extraction. Two kinds of marks emerge from one fissure: natural circular and organic forms (cinder cones, lava lakes, volcanic deposits) versus angular colonial geometries (mine shafts, transmission towers, nuclear facilities). How do we honor a landscape of such beauty and destruction while treading its terrain?

Sites Along the Lineament—Sacred Geometry in Trauma

Diablo Canyon | El Malpais | Mount Taylor | Los Alamos | White Rock Canyon | Valles Caldera

The lineament is both geological—deep crack in Earth allowing volcanism; & metaphorical—line of extraction across New Mexico.

Diablo Canyon: a 2.5-million-year-old lava lake that solidified and eroded into dramatic basalt cliffs. Part of a volcanic field with roughly 60 cinder cones, formed where the Rio Grande rift intersects the Jemez Lineament—structural weaknesses that opened pathways for magma to reach the surface. Diablo Canyon is located at the northern edge of the Caja del Rio near the Rio Grande.

A proposed 14-mile transmission line would cut through the Caja del Rio plateau—in the vicinity of Diablo Canyon—to power Los Alamos National Laboratory's supercomputers and nuclear weapons research, threading infrastructure for national security through landscapes held sacred by Pueblo communities. What nature patiently built over epochs, humans will damage in years for a nuclear facility.

Diablo Canyon, New Mexico

Power stations and transmission lines currently in place near Diablo Canyon.

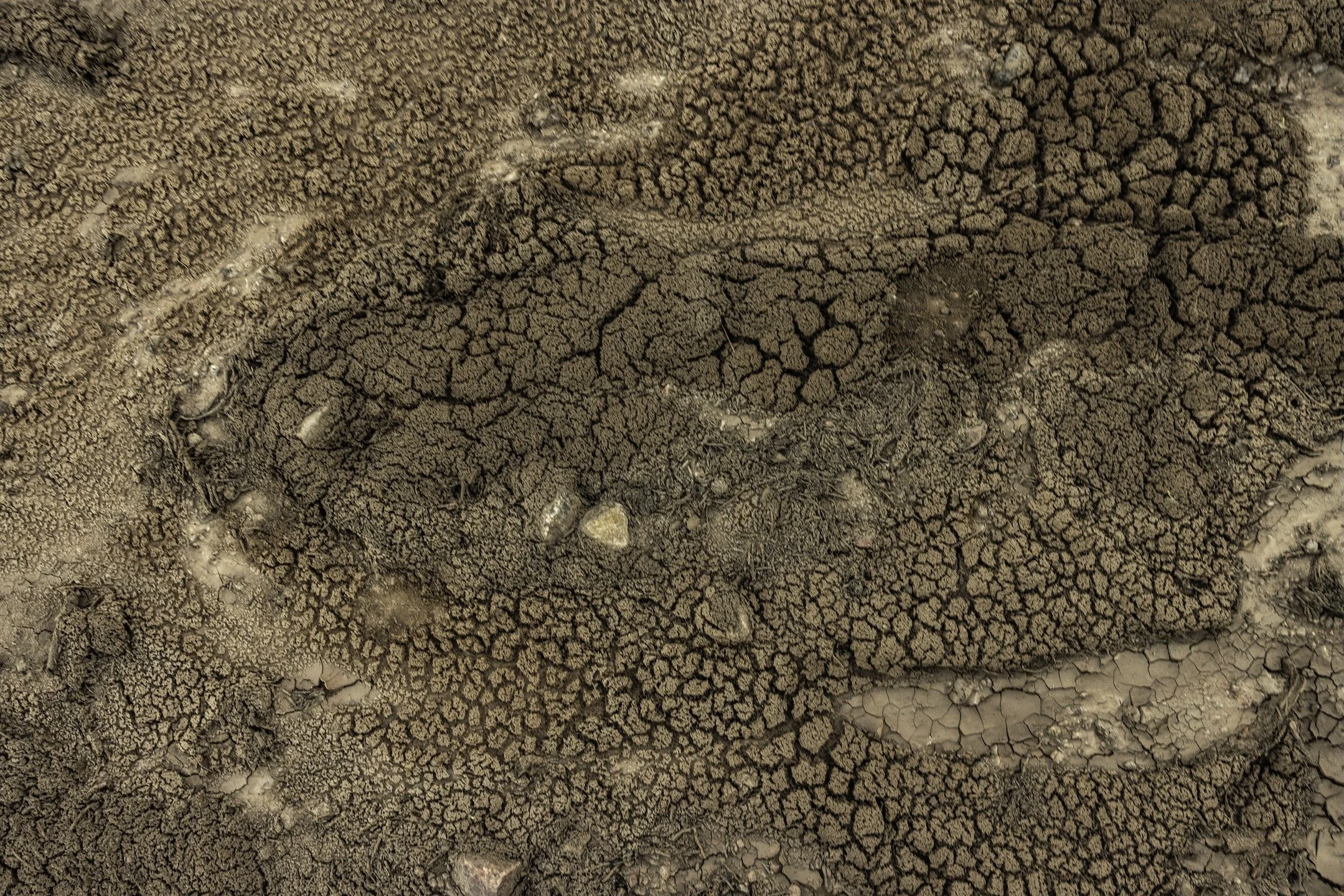

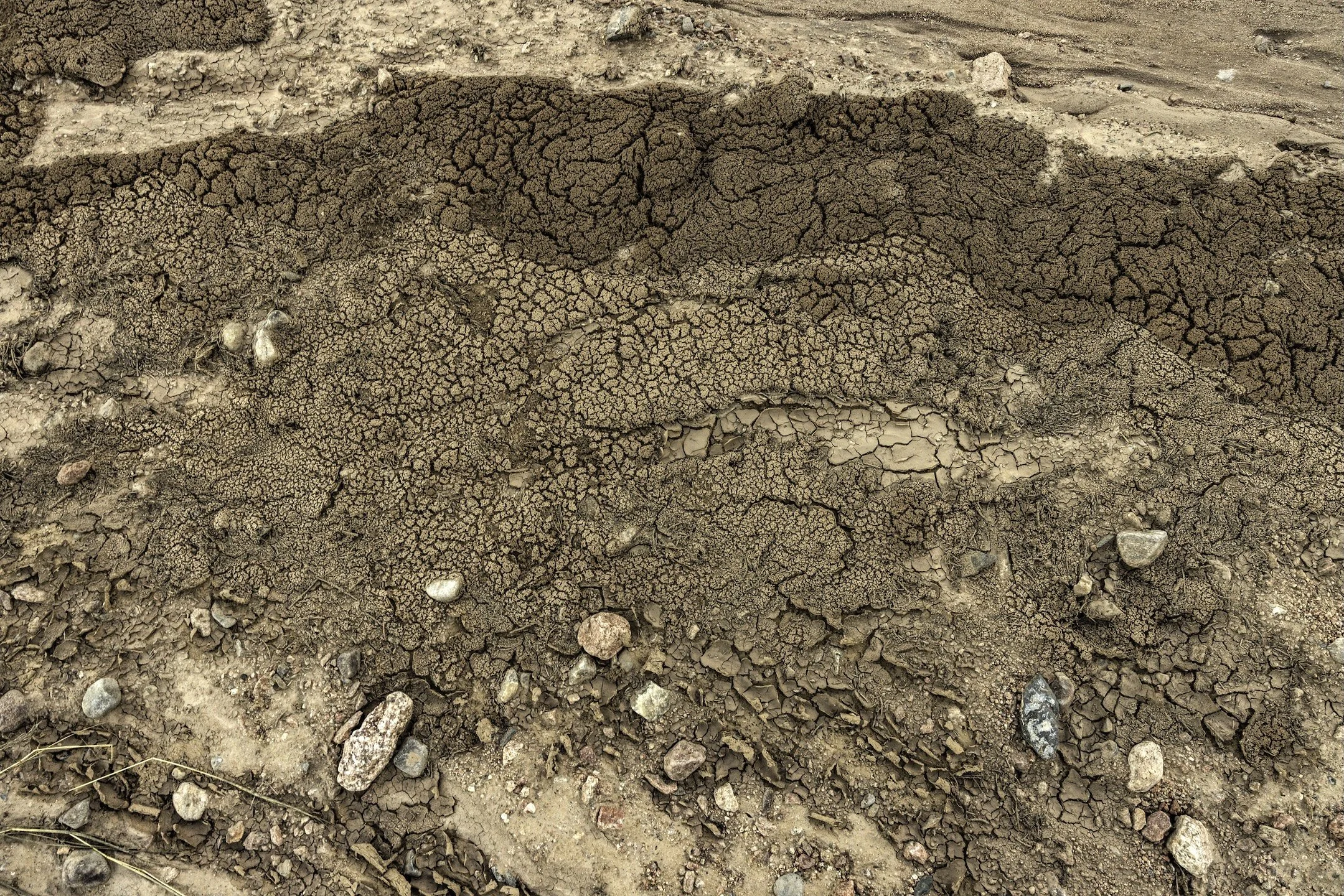

Soil at the Diablo Canyon

Soil at the Diablo Canyon

These photographs document cracked soil in the wash at the bottom of Diablo Canyon, New Mexico. The geometric fracture patterns map water's absence—the wash holds the ghost of water. Dry riverbeds serve as archives of flow while surface patterns testify to prolonged drought. In a landscape threatened by climate stress, the soil itself speaks, recording what persists and what waits.

Diablo Canyon

El Malpais: Spanish for "badlands," this landscape of black basalt flows, lava tubes, and numerous cinder cones along the Jemez Lineament contains some of North America's youngest lava—the McCartys flow is only 3,000 years old, still fresh with its glassy surface preserved. One walks across geological time measured in thousands rather than millions of years, volcanic violence so recent the landscape remains raw and unhealed.

Unlike Mount Taylor, Los Alamos, or Diablo Canyon where geological weakness becomes colonial opportunity, El Malpais offers a counterpoint: the same crustal fracture creating a landscape that is preserved, where geological violence transforms into wonder without extraction violence compounding it.

Lava Falls

Mount Taylor (Stratovolcano) Mount Taylor rises as a stratovolcano—built from countless eruptions layering lava, ash, and debris over millennia. Unlike monogenetic cinder cones, this mountain embodies repeated volcanic violence compounded into a sacred peak.

Then humans added their layers: uranium mines penetrating what indigenous communities hold sacred, extraction wounds carved into the volcano. The mountain holds all its histories simultaneously—geological, cultural, colonial—each layer inseparable from the others.

Mount Taylor view from Sandstone Bluffs, El Malpais

White Rock Canyon is a 900-foot gorge where the Rio Grande cuts through volcanic terrain—exposing both dark basalt from the Caja del Rio and pale Bandelier Tuff from the Pajarito Plateau—and holds hundreds of petroglyphs. This is where power transmission lines cross the Rio Grande, connecting Caja del Rio to Los Alamos.

Existing power infrastructure already spans the canyon, and the proposed new line would parallel these existing towers, threading more colonial infrastructure through a landscape that holds both geological and cultural significance. The canyon represents a literal and symbolic crossing point—where geological vulnerability becomes the pathway for human infrastructure to bridge sacred terrain.

Volcanic Forms—Formation, Fragmentation, Extraction

Cinder Cones / Diablo Canyon and El Malpais—simple, cone-shaped hills—form from single-vent eruptions, built from fragments rather than solid flow. Each cone marks one violent event; a field of cones records many eruptions—frozen moments of Earth's violence transformed into majestic beauty. They mirror my work: landscapes assembled from broken pieces, displacement, rebuilding from wreckage. Yet nature creates perfect geometric forms repeating in patterns across the field. Cinder cones are monogenetic—they erupt once and stop. Unlike uranium mining at Mount Taylor that extracts once but contaminates forever.

Basalt Cliffs / Diablo Canyon: Diablo Canyon's dramatic basalt cliffs formed when a lava lake solidified 2.5 million years ago, then eroded over millennia—creation through both deposition and removal. The towering walls expose Earth's subterranean depths brought to surface, carving a passage through geological time creating a natural wonder.

Lava Flows / Diablo Canyon and El Malpais: The lava flows spread as molten rivers, that cooled into textured black stone—solidifying into geometric columns, rope-like folds, or fragmented rubble. Each pattern records how the molten rock cooled and fractured. Like my work with fragmentation and reassembly, these natural landscapes parallel my process of breaking and creating new forms from fragments as a process of rebuilding life from wreckage.

Volcanic Tuff / White Rock Canyon The pale volcanic tuff cliffs at White Rock Canyon near Los Alamos formed from pyroclastic flows—superheated ash and gas that swept across the landscape, burying everything, then compressing into soft stone. This is landscape born from catastrophic eruption, air-borne destruction that settled and solidified. The tuff is fragile, easily carved and eroded, yet it holds ancient dwellings—Ancestral Puebloan homes carved into its softness. The same geological vulnerability that allowed people to carve homes also made this plateau ideal for nuclear research: remote, elevated, easily excavated. Creation and destruction inscribed in the same porous stone.

Resurgent Dome / Valles Caldera: After the catastrophic caldera collapse, the floor uplifted over 3,000 feet in 30,000 years, forming Redondo Peak—a mountain born from within the crater. This is the earth rebuilding itself from the inside, magma rising to fill the void left by eruption. The resurgent dome embodies rebirth after destruction, the landscape reassembling from its own fragmentation. Like my work with breaking and rebuilding, this geological process creates new form from collapse. Unlike extraction that hollows out mountains and leaves permanent voids, the resurgent dome shows the earth filling itself back up—geological trauma transforming into new topography, the caldera healing through its own volcanic forces.

Stained glass window at the United Church at Los Alamos. The Omega sign, the last letter of the Greek alphabet, symbolizes the“Great End.” Embedded in a mushrooming cloud, similar to the images of the first atom bomb created at Los Alamos and tested at Trinity site in New Mexico, the Omega symbol is directly under the Cross at the top, and has a crystal in the middle.

Among the 21 stained glass windows depicting biblical scenes, there are 3 untitled windows. This last one #21 is untitled.

A fellow resident at Santa Fe Art Institute, Felicia Honkasalo discovered this stained glass window, decoding its meaning.

Valles Caldera: At the intersection of the Rio Grande Rift and Jemez Lineament lies the source—a massive volcanic crater formed by supervolcano eruptions over a million years ago. These catastrophic eruptions created the Bandelier Tuff, the compressed volcanic ash that now forms the Pajarito Plateau where Los Alamos sits. This is the origin point of the volcanic violence that shaped every site along this lineament: the tuff that Ancestral Puebloans carved into, the plateau that Manhattan Project scientists chose for isolation, the geological weakness that opened pathways for both creation and extraction. Today, Valles Caldera is a National Preserve—a protected landscape like El Malpais, showing what the Lineament creates when left intact.

The caldera traces a conceptual arc through the project: from volcanic source, to volcanic ash carved into homes, to weaponized landscape built atop ancient eruptions. Walking this origin point means witnessing the beginning of geological trauma that later enabled colonial trauma.

Valles Caldera is a 13.7-mile-wide volcanic crater formed by two supervolcano eruptions 1.61 and 1.25 million years ago that together ejected approximately 150-200 cubic miles of magma into the stratosphere.

Los Alamos: Perched on the Pajarito Plateau—a volcanic tableland formed from pyroclastic flows (avalanches of superheated volcanic gas, ash, and rock fragments) along the Jemez Lineament—Los Alamos National Laboratory occupies what was once remote, forested terrain near Bandelier's ancient volcanic tuff canyons. Here, in 1945, scientists developed and built the first atomic bombs as part of the Manhattan Project, forever linking this geological landscape with nuclear weapons. Today, the laboratory is working to establish capacity to produce 30 plutonium pits annually for the nation's nuclear arsenal.

The same geological features that made this site remote and suitable for secret weapons research—the elevated plateau, the soft volcanic tuff easily excavated for facilities, the structural weakness of the Lineament providing isolation—have resulted in decades of contamination, forest clearing for power lines, and ongoing transformation of the landscape to serve nuclear infrastructure. Where volcanic eruptions once carved canyons and deposited ash, human activity now cuts corridors and buries radioactive waste, layering atomic violence onto geological landscape on the same ancient fracture line.

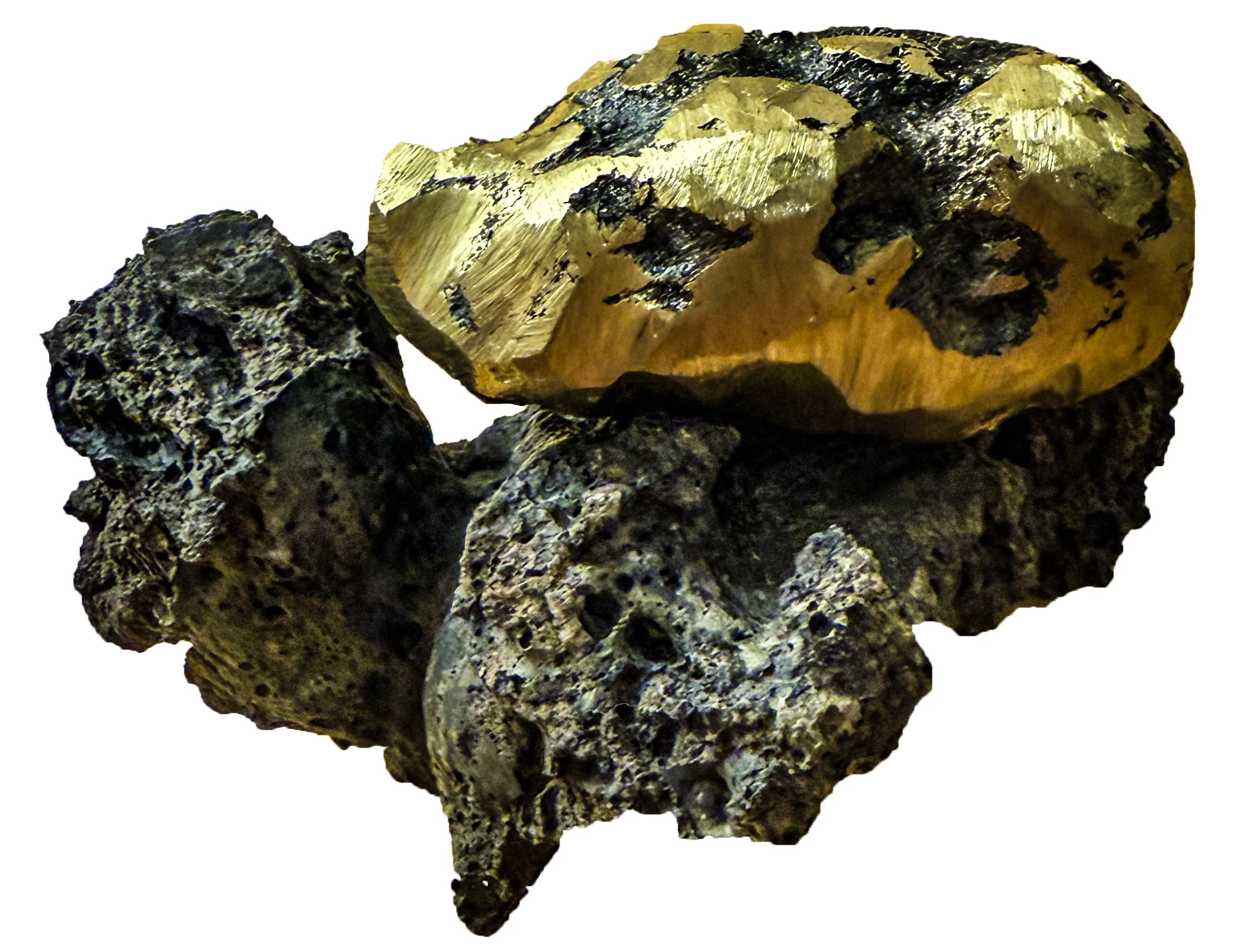

Copper cast of volcanic rock, New Mexico

Casting volcanic rocks from the Jemez Lineament in copper creates permanent records of geological forms threatened by extraction and landscape transformation. Using recycled copper breaks the extraction cycle while employing a material tied to New Mexico's colonial violence—copper mining since the early 1800s Spanish colonial period was inseparable from land theft, forced labor, and environmental destruction. Both copper casting and volcanic formation involve molten material from deep earth solidifying through intense heat, with one geological process (volcanism) preserved through another (metallurgy). These mobile impressions function as geological memories that acknowledge preservation's tension with extraction, using recycled materials to counter linear destruction while creating portable archives of vulnerable forms.

©2025 Sarah Ahmad. All Rights Reserved.